Molecular Structure of Nucleic Acids: A Structure for Deoxyribose Nucleic Acid ; Molecular Structure of Deoxypentose Nucleic Acids ; Molecular Configuration in Sodium Thymonucleate . Three papers in a single offprint from Nature, Vol. 171, No. 4356, April 25, 1953

WATSON, J. D. & CRICK, F. H. C.; WILKINS, M. H. F., STOKES, A. R. & WILSON, H. R.; FRANKLIN, R. E. & GOSLING, R. G.

Librería:

SOPHIA RARE BOOKS, Koebenhavn V, Dinamarca

Calificación del vendedor: 5 de 5 estrellas

![]()

Vendedor de AbeBooks desde 18 de enero de 2013

Descripción

Descripción:

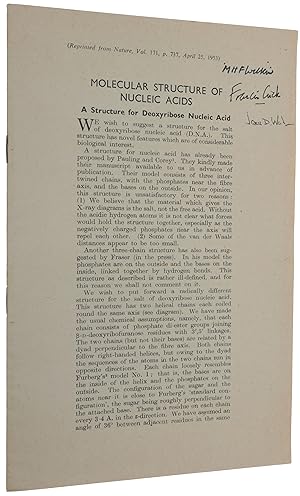

DISCOVERY OF THE STRUCTURE OF DNA. SIGNED BY ALL BUT ONE OF THE AUTHORS. First edition, offprint, signed by Watson, Crick, Wilkins, Gosling, Stokes & Wilson, i.e. six of the seven authors. We know of no copy signed by Franklin, and strongly doubt that any such copy exists. Furthermore this copy is, what we believe to be, just one of three copies signed by six authors. One of the most important scientific papers of the twentieth century, which "records the discovery of the molecular structure of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA), the main component of chromosomes and the material that transfers genetic characteristics in all life forms. Publication of this paper initiated the science of molecular biology. Forty years after Watson and Crick s discovery, so much of the basic understanding of medicine and disease has advanced to the molecular level that their paper may be considered the most significant single contribution to biology and medicine in the twentieth century" (One Hundred Books Famous in Medicine, p. 362). "The discovery in 1953 of the double helix, the twisted-ladder structure of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA), by James Watson and Francis Crick marked a milestone in the history of science and gave rise to modern molecular biology, which is largely concerned with understanding how genes control the chemical processes within cells. In short order, their discovery yielded ground-breaking insights into the genetic code and protein synthesis. During the 1970s and 1980s, it helped to produce new and powerful scientific techniques, specifically recombinant DNA research, genetic engineering, rapid gene sequencing, and monoclonal antibodies, techniques on which today s multi-billion dollar biotechnology industry is founded. Major current advances in science, namely genetic fingerprinting and modern forensics, the mapping of the human genome, and the promise, yet unfulfilled, of gene therapy, all have their origins in Watson and Crick s inspired work. The double helix has not only reshaped biology, it has become a cultural icon, represented in sculpture, visual art, jewelry, and toys" (Francis Crick Papers, National Library of Medicine, profiles./SC/Views/Exhibit/narrative/). In 1962, Watson, Crick, and Wilkins shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine "for their discoveries concerning the molecular structure of nucleic acids and its significance for information transfer in living material." This copy is signed by all the authors except Rosalind Franklin (1920 1958) - we have never seen or heard of a copy signed by her. In 1869, the Swiss physiological chemist Friedrich Miescher (1844-95) first identified what he called nuclein inside the nuclei of human white blood cells. (The term nuclein was later changed to nucleic acid and eventually to deoxyribonucleic acid, or DNA. ) Miescher s plan was to isolate and characterize not the nuclein (which nobody at that time realized existed) but instead the protein components of leukocytes (white blood cells). Miescher thus made arrangements for a local surgical clinic to send him used, pus-coated patient bandages; once he received the bandages, he planned to wash them, filter out the leukocytes, and extract and identify the various proteins within the white blood cells. But when he came across a substance from the cell nuclei that had chemical properties unlike any protein, including a much higher phosphorous content and resistance to proteolysis (protein digestion), Miescher realized that he had discovered a new substance. Sensing the importance of his findings, Miescher wrote, "It seems probable to me that a whole family of such slightly varying phosphorous-containing substances will appear, as a group of nucleins, equivalent to proteins". But Miescher s discovery of nucleic acids was not appreciated by the scientific community, and his name had fallen into obscurity by the 20th century. "Researchers working on DNA in the early 1950s used the term gene to mean the smallest u. N° de ref. del artículo 5470

Detalles bibliográficos

Título: Molecular Structure of Nucleic Acids: A ...

Editorial: Fisher, Knight & Co, St. Albans

Año de publicación: 1953

Ejemplar firmado: Firmado por el autor

Edición: First edition.

Los mejores resultados en AbeBooks

'Molecular Structure of Nucleic Acids: A Structure for Deoxyribose Nucleic Acid'; 'Molecular Structure of Deoxypentose Nucleic Acids'; 'Molecular Configuration in Sodium Thymonucleate'. Three papers in a single offprint from Nature, Vol. 171, No. 4356, April 25, 1953

Librería: SOPHIA RARE BOOKS, Koebenhavn V, Dinamarca

First edition. DISCOVERY OF THE STRUCTURE OF DNA. First edition, in the rare offprint form, of one of the most important scientific papers of the twentieth century, which "records the discovery of the molecular structure of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA), the main component of chromosomes and the material that transfers genetic characteristics in all life forms. Publication of this paper initiated the science of molecular biology. Forty years after Watson and Crick's discovery, so much of the basic understanding of medicine and disease has advanced to the molecular level that their paper may be considered the most significant single contribution to biology and medicine in the twentieth century" (One Hundred Books Famous in Medicine, p. 362). "The discovery in 1953 of the double helix, the twisted-ladder structure of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA), by James Watson and Francis Crick marked a milestone in the history of science and gave rise to modern molecular biology, which is largely concerned with understanding how genes control the chemical processes within cells. In short order, their discovery yielded ground-breaking insights into the genetic code and protein synthesis. During the 1970s and 1980s, it helped to produce new and powerful scientific techniques, specifically recombinant DNA research, genetic engineering, rapid gene sequencing, and monoclonal antibodies, techniques on which today's multi-billion dollar biotechnology industry is founded. Major current advances in science, namely genetic fingerprinting and modern forensics, the mapping of the human genome, and the promise, yet unfulfilled, of gene therapy, all have their origins in Watson and Crick's inspired work. The double helix has not only reshaped biology, it has become a cultural icon, represented in sculpture, visual art, jewelry, and toys" (Francis Crick Papers, National Library of Medicine, profiles./SC/Views/Exhibit/narrative/). In 1962, Watson, Crick, and Wilkins shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine "for their discoveries concerning the molecular structure of nucleic acids and its significance for information transfer in living material." In 1869, the Swiss physiological chemist Friedrich Miescher (1844-95) first identified what he called 'nuclein' inside the nuclei of human white blood cells. (The term 'nuclein' was later changed to 'nucleic acid' and eventually to 'deoxyribonucleic acid,' or 'DNA.') Miescher's plan was to isolate and characterize not the nuclein (which nobody at that time realized existed) but instead the protein components of leukocytes (white blood cells). Miescher thus made arrangements for a local surgical clinic to send him used, pus-coated patient bandages; once he received the bandages, he planned to wash them, filter out the leukocytes, and extract and identify the various proteins within the white blood cells. But when he came across a substance from the cell nuclei that had chemical properties unlike any protein, including a much higher phosphorous content and resistance to proteolysis (protein digestion), Miescher realized that he had discovered a new substance. Sensing the importance of his findings, Miescher wrote, "It seems probable to me that a whole family of such slightly varying phosphorous-containing substances will appear, as a group of nucleins, equivalent to proteins". But Miescher's discovery of nucleic acids was not appreciated by the scientific community, and his name had fallen into obscurity by the 20th century. "Researchers working on DNA in the early 1950s used the term 'gene' to mean the smallest unit of genetic information, but they did not know what a gene actually looked like structurally and chemically, or how it was copied, with very few errors, generation after generation. In 1944, Oswald Avery had shown that DNA was the 'transforming principle,' the carrier of hereditary information, in pneumococcal bacteria. Nevertheless, many scientists continued to believe that DNA had a structure too uniform and simple to store genetic information for making complex living organisms. The genetic material, they reasoned, must consist of proteins, much more diverse and intricate molecules known to perform a multitude of biological functions in the cell. "Crick and Watson recognized, at an early stage in their careers, that gaining a detailed knowledge of the three-dimensional configuration of the gene was the central problem in molecular biology. Without such knowledge, heredity and reproduction could not be understood. They seized on this problem during their very first encounter, in the summer of 1951, and pursued it with single-minded focus over the course of the next eighteen months. This meant taking on the arduous intellectual task of immersing themselves in all the fields of science involved: genetics, biochemistry, chemistry, physical chemistry, and X-ray crystallography. Drawing on the experimental results of others (they conducted no DNA experiments of their own), taking advantage of their complementary scientific backgrounds in physics and X-ray crystallography (Crick) and viral and bacterial genetics (Watson), and relying on their brilliant intuition, persistence, and luck, the two showed that DNA had a structure sufficiently complex and yet elegantly simple enough to be the master molecule of life. "Other researchers had made important but seemingly unconnected findings about the composition of DNA; it fell to Watson and Crick to unify these disparate findings into a coherent theory of genetic transfer. The organic chemist Alexander Todd had determined that the backbone of the DNA molecule contained repeating phosphate and deoxyribose sugar groups. The biochemist Erwin Chargaff had found that while the amount of DNA and of its four types of bases the purine bases adenine (A) and guanine (G), and the pyrimidine bases cytosine (C) and thymine (T) varied widely from species to species, A and T always appeared in ratios of one-to-one, as did G and C. Maurice Wilkins an. Nº de ref. del artículo: 6370

Comprar usado

Se envía de Dinamarca a Estados Unidos de America

Cantidad disponible: 2 disponibles

Molecular Structure of Nucleic Acids: A Structure for Deoxyribose Nucleic Acid; Molecular Structure of Deoxypentose Nucleic Acids; Molecular Configuration in Sodium Thymonucleate; Three papers in a single offprint from Nature, Vol. 171, No. 4356, April 25, 1953

Librería: Biblioctopus, Los Angeles, CA, Estados Unidos de America

Condición: Near fine. First Edition. First edition, the three-paper offprint issue, of the primary record of the co-discovery of the molecular structure of DNA, the most transformative moment in twentieth-century biology. Octavo, pp. 14. with two diagrams (including the double helix) and two illustrations from photographs. Stapled in self-wrappers as issued. Signed by Maurice Wilkins on the first page. Very lightly toned and a coulpe soft creases, near fine. Grolier Club, One Hundred Books Famous in Medicine, 99; Dibner, Heralds of Science, 200. Garrison-Morton 256.3; Judson, Eighth Day of Creation, pp. 145-56. Ex-Dr. Myron Printzmetal. The discovery of DNA's double helix structure emerged from an intense period of competitive collaboration between research teams at Cambridge and King's College London. Watson and Crick's theoretical breakthrough synthesized crucial experimental evidence from multiple sources: Erwin Chargaff's base composition rules demonstrating the 1:1 ratio of adenine to thymine and guanine to cytosine, X-ray crystallographic data revealing DNA's helical structure, and most critically, the precise measurements of backbone positioning and molecular dimensions. Their elegant model proposed complementary base pairing (A-T and C-G) held together by hydrogen bonds, immediately suggesting a mechanism for genetic replication where each strand could serve as a template for its complement. The accompanying papers by Wilkins, Stokes, and Wilson, and by Franklin and Gosling, provided essential experimental validation through X-ray diffraction analysis, creating a unified presentation of both theoretical insight and empirical evidence that established the foundation of molecular biology. The contentious history surrounding this discovery has generated enduring scholarly debate, particularly regarding the systematic marginalization of Rosalind Franklin's contributions. Franklin's meticulous X-ray crystallographic work, conducted with her graduate student Raymond Gosling, had independently determined many key structural features including the antiparallel orientation of DNA strands, the external positioning of phosphate groups, and precise helical parameters. Her famous "Photograph 51" provided definitive evidence of DNA's helical structure, while her systematic analysis of A-form and B-form DNA revealed critical dimensions that enabled Watson and Crick's model construction. As Brenda Maddox documents in "Rosalind Franklin: The Dark Lady of DNA," Franklin's data was shown to Watson and Crick without her knowledge through Maurice Wilkins, creating an ethical controversy that persists in discussions of scientific collaboration and gender bias. Franklin's death from ovarian cancer in 1958, four years before the Nobel Prize was awarded to Watson, Crick, and Wilkins, has intensified debates about recognition and the complex dynamics of mid-twentieth century scientific discovery, with many scholars arguing that her rigorous experimental approach was as fundamental to the breakthrough as the theoretical modeling that received greater acclaim. This publication represents the founding document of modern molecular biology, establishing the conceptual framework for understanding heredity, genetic replication, and the molecular basis of life itself. The discovery immediately suggested mechanisms for protein synthesis and genetic information transfer, creating the theoretical foundation for subsequent developments in genetic engineering, biotechnology, and genomic medicine. As Francis Crick later observed, the structure's elegant simplicitywith its complementary base pairing and antiparallel strandsprovided not merely a static model but a dynamic mechanism explaining how genetic information could be accurately copied and transmitted across generations. The offprint's scientific significance extends far beyond its immediate discovery, representing the moment when biology transformed from a primarily descriptive science into a molecular discipline capable of manipulating the fundamental mechanisms of life, establishing the intellectual foundation for the biotechnology revolution that continues to reshape medicine, agriculture, and our understanding of evolutionary processes seventy years after its publication. Nº de ref. del artículo: 1192

Comprar usado

Se envía dentro de Estados Unidos de America

Cantidad disponible: 1 disponibles