MEDIEVAL ART ALL MEDIEVAL HISTORICAL DOCUMENTS (5 resultados)

ComentariosFiltros de búsqueda

Tipo de artículo

- Todos los tipos de productos

- Libros (5)

- Revistas y publicaciones (No hay ningún otro resultado que coincida con este filtro.)

- Cómics (No hay ningún otro resultado que coincida con este filtro.)

- Partituras (No hay ningún otro resultado que coincida con este filtro.)

- Arte, grabados y pósters (No hay ningún otro resultado que coincida con este filtro.)

- Fotografías (No hay ningún otro resultado que coincida con este filtro.)

- Mapas (No hay ningún otro resultado que coincida con este filtro.)

- Manuscritos y coleccionismo de papel (No hay ningún otro resultado que coincida con este filtro.)

Condición Más información

- Nuevo (No hay ningún otro resultado que coincida con este filtro.)

- Como nuevo, Excelente o Muy bueno (No hay ningún otro resultado que coincida con este filtro.)

- Bueno o Aceptable (No hay ningún otro resultado que coincida con este filtro.)

- Regular o Pobre (No hay ningún otro resultado que coincida con este filtro.)

- Tal como se indica (5)

Encuadernación

- Todas

- Tapa dura (1)

- Tapa blanda (No hay ningún otro resultado que coincida con este filtro.)

Más atributos

- Primera edición (No hay ningún otro resultado que coincida con este filtro.)

- Firmado (No hay ningún otro resultado que coincida con este filtro.)

- Sobrecubierta (No hay ningún otro resultado que coincida con este filtro.)

- Con imágenes (5)

- No impresión bajo demanda (5)

Idioma (1)

Precio

- Cualquier precio

- Menos de EUR 20 (No hay ningún otro resultado que coincida con este filtro.)

- EUR 20 a EUR 45 (No hay ningún otro resultado que coincida con este filtro.)

- Más de EUR 45

Gastos de envío gratis

- Envío gratis a España (No hay ningún otro resultado que coincida con este filtro.)

Ubicación del vendedor

Valoración de los vendedores

-

Julius Caesar's Invasion of Britain: An Historic Illumination From a Now Lost 15th Century Work (A Medieval Miniature of Julius Caesar Routing the Chariot-Mounted Forces of the British Chieftain Cassivellaunus During Rome?s 2nd Expedition to England)

Librería: The Raab Collection, Ardmore, PA, Estados Unidos de America

EUR 16.444,60

Convertir monedaEUR 9,92 gastos de envío desde Estados Unidos de America a EspañaCantidad disponible: 1 disponibles

Añadir al carritoThe sole known surviving piece of a once vast and grand 15th century "Faits des Romans," doubtless for a noble patron of enormous wealth.?The artist is a follower of the Co?tivy MasterThe twin nostalgias of Europe? one for the powerful, all-encompassing Roman Empire, the other for connecting with the mysterious pre-Roman peoples? combine in this 15th century French illumination of Caesar?s final, and questionably successful, encounter with the Britons, led by Cassivellaunus. While Caesar won this battle, his dream of a conquered, and Roman, Britain would not be realized within his lifetime. His legacy, however, was studied, admired, and immortalized far after his fatal betrayal by Brutus. This illustration captures this historic moment of Caesar?s triumph, the beginning of the end for the Britons, and the cultural legacy as viewed during the waning of the Middle Ages.In the nineteenth century, European medievalists began shoring up their nations? relationships with medieval literature to try to create firm claims of their peoples? innate heroic attributes, their noble histories, their glorious pasts. This led, for example, to the French identifying themselves with the Chanson de Roland and the English lionizing King Arthur. But the desire to have these medieval roots overshadowed the more complicated histories: the Chanson de Roland, though composed in French, is about an emperor best known by his French name, Charlemagne, but who was born in Aachen, Germany and is buried there. The first legends of King Arthur from the 9th century, reflecting a much earlier time, came from Wales, a nation suppressed by the English, and the major inventions in the narrative, like the love story of Guinevere and Lancelot, and the Round Table, were invented in France. Though English storytellers engaged with Arthur and his knights, it wasn?t until Thomas Malory in the 15th century that Arthur became English.During the Middle Ages, Rome was the empire to draw connections to for auctoritas. This is why the empire established by Charlemagne became known as the Holy Roman Empire. Though the term was not in use until the 13th century, the Emperors were instilled with translation imperii-- a transfer of rule directly inherited from the historic emperors of Rome.One aspect of Rome that was particularly admired in the Middle Ages was the conquering and bringing into Civilization of the barbarians north of the Alps and west of the Rhine, that includes Caesar's foray into England and his confrontation with Cassivellanus. Cassivellaunus was likely the chief of the Catuvellauni of Hertfordshire, whose tribal name translates to ?war-chiefs? In British accounts, he appears in Welsh literature ranging from Geoffrey of Monmouth?s chronicle about the history of the Kings of Britain in both Latin, Historia regum Britanniae, and Welsh, Brut y Brenhinedd, to the more folkloric-based Trioedd Ynys Prydein (The Triads), the second branch of the Mabinogi, and Cyfranc Lludd a Llefelys (The Adventure of Lludd and Llefelys). The British chieftain even appears, briefly, in the Greek Stratagemata by Polyaenus. The Latin literature, of course, written by the winners, includes Julius Caesar?s own Commentary de Bello Gallico (Commentary on the Gallic War).During the account of his second campaign in Britain from Gaul in 54 BCE, after a failed first a year earlier, Caesar writes that Cassivellaunus was a rabble-rouser, conquering the Trinovantes, the most powerful British tribe (perhaps how the tribe received their appellation of ?war-chiefs?). Though his location was betrayed by the Cenimagni, Segontiaci, Ancalites, Bibroci, and Cassi, who had surrendered to Caesar, Cassivellaunus gathered the forces of the Kentish kings, Cinetorix, Varvilius, Taximagulus, and Segovax. The tribes retreated to higher ground when they saw the sheer masses of Romans that Caesar had brought to avert the same failure of preparedness he suffered the year before. The legions established their militar.

-

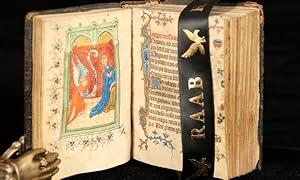

An Early, Petite Devotional Manuscript Book of Hours Painted in Bruges at the Beginning of the 15th century, Perhaps Owned by a Patron with Connections to Bologna (With five fine full-page miniatures by the same artist responsible for a similar work at the Nuremberg City Library)

Librería: The Raab Collection, Ardmore, PA, Estados Unidos de America

EUR 35.555,89

Convertir monedaEUR 9,92 gastos de envío desde Estados Unidos de America a EspañaCantidad disponible: 1 disponibles

Añadir al carritoBooks of Hours, private devotional books, intended to guide their reader through the various hours of daily prayer, emerged from the Psalter, a book used by monks and nuns to order their daily devotions. From the fourteenth century, wealthy lay-people began to increasingly want to take part in these regular acts of prayer, and so a demand was created for similar books aimed at the laity. These had twin aims ? to aid the user in their prayers, for which a set system of prayers and aids to these was developed (though variable depending on location) - and to demonstrate the wealth and influence of the owner, leading to increasingly more decoration and large devotional images, often by professional artists or workshops dedicated to the production of these books. This type of book was steadily produced in continually increasing numbers throughout the Middle Ages into the Early Modern period, becoming something of a medieval ?bestseller? ? certainly it was the type of book through which the highest number of Europeans in the Middle Ages came into contact with the Bible and prayer, and in many cases was the only book that a non-ecclesiastic would own.[video width="1920" height="1080" mp4="https://cdn.raabcollection.com/wp-content/uploads/202312041 22316/Book-of-hours.mp4"][/video]?The present book has illumination showing that our manuscript was made in Bruges in the first years of the 15th century: the Virgin of Humility on f.39v, shown seated on a cushion with her feet on a crescent moon, is an iconographical choice distinct to Bruges. Many Bruges books were intended for export to England, but the liturgical use ? of Rome, not Sarum ? and an absence of English saints such as Edmund, Oswald and Hugh of Lincoln in the Calendar, shows instead that this book was produced for the home market in the Low Countries. The unusual inclusion of the Italian saint Proculus of Bologna in the Litany, placed a prominent second in the list of martyrs, might point instead to an Italian patron, or one with Bolognese heritage or business connections in Bologna.The cool palette, rather stiff figures, and a preference for red backgrounds link these Hours stylistically to the 'Ushaw Group', active at the beginning of the 15th century in Bruges, the most important centre of manuscript production in the Southern Netherlands at this time. Named for a Book of Hours in Durham (Ushaw College MS 10) with a colophon by the copyist Johannes Heineman stating that it was written in Bruges and completed in January 1409, the Ushaw Group were responsible for a wide corpus of manuscripts dateable to roughly 1400-1415 (for the Ushaw Group and Bruges manuscripts of the period, see M. Smeyers, Flemish Miniatures, 1999, pp. 194-214). Our manuscript seems to have been painted by the same artist as a Book of Hours now in N?rnberg (Stadtbibliothek, Hert. Ms. 3; see Smeyers, p.198).Anonymous Bruges artist, Book of Hours, use of Rome, in Latin, illuminated manuscript on vellum [Bruges, c.1400-1415], 104 x 80mm.160 + i, collation: 112, 29 (of 8, i an inserted miniature), 39 (of 8, i an inserted miniature), 49 (ix a singleton), 59 (of 8, i an inserted miniature), 6-98, 1010 (of 12, xi-xii cancelled blanks), 114, 129 (of 9, i an inserted miniature), 138, 149 (of 8, i an inserted miniature), 15-188, 19-204, 15 lines, ruled space: 65 x 42mm, rubrics in red, one-line initials alternating blue and liquid gold and two-line illuminated initials on blue grounds throughout, 14 illuminated initials with borders of bars, ivy and hairline tendrils supporting flowers and gold discs, five full-page miniatures within frames topped with architectural arches with border decoration of gold discs on hairline tendrils (a little cropped, scattered light staining throughout).A Calendar of saints and their feastdays along with other important feasts ff.1-12; the Hours of the Cross (a daily cycle of prayers in honour of the Cross) ff.14-16; the Hours of the Holy Spirit (a daily cycle of prayers in honour.

-

A Medieval 12th Century Illustration of a French Hunter, His Dog, and Their Catch: A Hare (We were unable to find other such early examples of Medieval hunters and their pets having reached the market)

Librería: The Raab Collection, Ardmore, PA, Estados Unidos de America

EUR 9.333,42

Convertir monedaEUR 9,92 gastos de envío desde Estados Unidos de America a EspañaCantidad disponible: 1 disponibles

Añadir al carritoMedieval canine companionship: remarkably early inhabited initial of a dog; from 12th Century FranceEx-Parke Bernet, 1948?Mankind has long been infatuated with dogs. The canine/human relationship goes back tens of thousands of years, and a painting of a dog as cave art from 9,000 years ago has survived. But it was only in the Middle Ages that images of dogs, especially those in context, begin to appear with any regularity.?Dogs? roles in the lives of humans from the Middle Ages would be familiar to us in the modern day. Besides being lap dogs or companions, dogs also helped in the hunt.Throughout the Middle Ages, important thinkers turn their thoughts towards animals, both allegorical and figural. As early as Pliny the Elder, who wrote Natural History around 70 AD, the loyalty of our canine companions has been noted, with anecdotes of dogs staying by their owner?s sides even after death. This theme is carried through the Middle Ages and the 14th century, and the ?author of the Goodman of Paris also claims to have even seen with his own eyes a case of canine loyalty unto death? (Medieval Pets 9). In the 6th century, Saint Gregory the Great wrote in his Homilies on the Evangelists, comparing preachers with dogs in that the tongues of both have the power to cure. Though Isidore of Seville?s encyclopaedic text, Etamologiae, was written in the 7th century, it stands as a standard text for medieval scholarship and understanding of the natural world. Isidore?s entry for dogs underscores two qualities: bravery and speed. Chaucer includes a charming description of the Prioress, that ?of small hounds she had and fed with with roasted flesh or milk or wasted-bread. But sorely she would weep if one of them were dead, or if someone hit it smartly with a stick.?The difference between working dogs and pet dogs, primarily, was size, with lap-dogs being thought to be close to the modern Bichon, spaniels, and ?small scent hounds,? such as greyhounds (Pets, 5). Though John Caius? On Canibus Britannicis (On British Dogs) appears later than our present dog, it remains an important resource for understanding pre-Modern dogs. He lists out hunting dog breeds as ?the Harier, the Terrar, the Bloudhounde, the Gasehounde, the Grehounde, the Leuiner or Lyemmer, [and] the Tumbler.? The accoutrement accompanying pet and working dogs differed. The collars of lap dogs, for example, were ornamented with precious metals and bells (Medieval Pets, 51-2).Hunting dogs and lap dogs would also receive different meals, with lap dogs begetting from the luxury of milk??The accounts of Eleanor de Montfort (1258?82) in 1265 include entries for her chamberlain purchasing milk for her pet dogs that lived in her chamber. The household?s hunting dogs that were kennelled outside would not have received milk, although all the dogs ate bread.?(Medieval Pets, 42)Gift-giving in court was common and occasionally included the gift of a hound. These hounds were frequently gifted with the intention of being hunting dogs. These dogs may have occasionally been invited in to the lap and turned into pets by their new owners (Medieval Pets, 24). We have a terrific amount of information regarding the naming of dogs in the Middle Ages. Some dogs were named after their breed, some after famous knights and other figures of literature. According to the records of the shooting-festival in Zurich in 1504, the most popular dog name was F?rst, which translates to Prince.King Charles IX of France?s La chase royale, writing in the 16th century but illuminating earlier hunting techniques, there were ?three basic strains? of dog: black, white, and grey (The Hound and the Hawk, 16).The white, Charles IX tells us, originated at St. Hubert; and the grey has the benefit of being immune to rabies, but was thought to be less sensitive to scent. Charles? anecdote on the grey dog?s origins date to King Louis? conquering of the Holy Land, where he came across a breed of dog in Tartary and brought them back to F.

-

A Medieval 12th Century Depiction of a Saint, Likely Created in Southern France (Such early illustrations are not common on the market)

Librería: The Raab Collection, Ardmore, PA, Estados Unidos de America

EUR 5.333,38

Convertir monedaEUR 9,92 gastos de envío desde Estados Unidos de America a EspañaCantidad disponible: 1 disponibles

Añadir al carritoRecords of the sale of this piece date back to the 1940s at a sale at Parke Bernet in New York, which noted its rarityAcross Europe, holy wells dot the landscape, often renamed and repurposed from pre-Christian sites of worship. Relics of finger bones and tunics are carefully and reverently shrouded in the churches. Pilgrims walk the same paths year after year to atone for their sins and contemplate God. Effigies or symbols are carried around for specific protections. Hagiographies, also called vitae or lives, detailed holy lives and were written down in jewel-covered manuscripts. In short, saints and saints? cults navigated the social and political sphere, even the geography, of medieval Europe.Some saints were responsible for specific requests of intercession. Saint Sigismund, the 6th century King of the Burgundians, cured fevers and was the first saint to ?specialise in the cure of a particular medical condition? (Paxton, 26). Before Saint Sigismund, in order to pray for a saint?s favour, pilgrims would have to visit the shrine of the particular saint. Because the petition to cure fever was addressed to Sigismund through the votive mass, ?Missa sancti Sigismundi?, suffers could pray to him from anywhere and receive his succour with the help of their own priests. Sigismund?s path to sainthood is another interesting case of the sometimes unusual aspects of medieval saints? cults. Despite being ?a layman who had not died in the defense of his faith? and having ?had one of his sons ruthlessly murdered? (Paxton, 28), Sigismund ?gained the reputation as a saint and as a source of healing power over fevers? (Paxton, 25). Sigismund had founded an Abbey of Agaune during his lifetime, and the monks residing there took the opportunity in the late 6th century to promote the posthumous healing powers of their founder (N_st_soiu, 589). Gregory of Tours praised Sigismund?s effectiveness over fevers in his Liber in Gloria Martyrum and thus, a saint was made.Litanies and hagiographies, or the biographies of saints (from the Greek for holy writings), give a sense of the array of local saints, like Sigismund, and standard saints that would have been recognised across the Medieval Christian world, like the Martyrs or the Apostles. Based on scholarship that has laboured to compile comprehensive lists of saints, the Bibliotheca sanctorum provides 20,000 saints from the early Medieval to the Reformation period, with 15,000 of them from the early Christian and Medieval period (Bartlett, 137).Illustrated initial of a Saint, France, likely Southwest, Twelfth century, 90 by 125mm, an 'I' formed from a standing saint in green, white, red, and blue robes. Reverse, what remains of text in Romanesque hand with two letters touched in red, ST ligature.Originally, this miniature, historically excised from a 12th century Southern French manuscript, would have stood as an illuminated initial, beginning a word starting with the capital letter I. We can tell that this figure represents a saint because of the plane halo and his hand with two fingers stretched out in a blessing. In his other hand he grasps what could be a scroll or a pouch. Unfortunately, the illuminator did not include identifying features? for example, we know Saint Christopher because he is usually depicted carrying the Christ child (as Christoforos means carrier of Christ), or Saint Katherine is depicted with the instrument of her torture, a wheel. Close examination of the saint?s face reveals that his mouth is open, likely to speak a blessing or respond to a supplicant?s request in conjunction with his gesture.While the identity of the saint depicted in this miniature may be lost among the 15,000 possibilities, perhaps his clothing give us more sense of his holiness. According to early Irish monks, three kinds of martyrdom were possible: white, green, and red. The monks described white martyrdom as a cutting off from the things he loves; green martyrdom is through fasting and labor, a separa.

-

A Provocative Late Medieval Portrait of English Dominican Friar, from the 15th Century (The wear in one particular spot reflects the toll of the owner?s ritual touching of the Virgin?s face in conjunction with his portrait, similar to the touching of a medallion or cross)

Librería: The Raab Collection, Ardmore, PA, Estados Unidos de America

EUR 5.333,38

Convertir monedaEUR 9,92 gastos de envío desde Estados Unidos de America a EspañaCantidad disponible: 1 disponibles

Añadir al carritoIt is unusual to find an English example, particularly one which so well demonstrates the unique factors at play in such pieces at the timeThroughout the Middle Ages, true visionaries put into place systems of intellectual and social organisation. Saint Dominic?s foundation of the Dominican Order responded to a need for a new kind of monasticism, as Medieval Europe shifted towards an increased urbanisation, which would give rise to the great cities that we now know. In the city of Toulouse, France, Dominic based his Order on the Rule of Saint Augustine? a system of tenets to organize the lives of the monks which focused heavily on salvation through preaching. Dominic?s order valued education as the vehicle for effective preaching, and therefore effective saving of souls. Dominic?s vision saw his followers establishing schools alongside newly burgeoning universities in Paris and Bologna, and later in Palencia, Montpellier, and even Oxford within his lifetime. Members of the Dominican Order took their message of educated understanding of God from the continent to the British Isles, settling in Oxford by 1221.Thomas Aquinas and Albertus Magnus were also of the Dominican Order.Given the wealth of expressions of interiority that arise in [later Medieval] arts, . scholars, philosophers, and ideologues have often turned to this era when seeking the putative origins of modern selfhood" (Sands 1); the inclusion of patron portraits acts as a reflection of the self reflecting on the divine, personalizes the book. After book productions shifted towards catering to the wealthy rather than the monastic, lay-patrons were able to emulate "monastic patterns of reading, prayer, and meditation" (Sands 15). Rather than allowing a wealthy lay patron to emulate the monastic way of life, the patron portrait of this Dominican monk is a glimpse into the monastic way of life and an individual's development of his sense of self.This leaf, from a Dominican?s personal prayer book, features a portrait of the owner himself. This little peak into a 15th century private sphere shows the book?s owner depicted in his traditional black cloak? which gave rise to the appellation of the Dominicans as ?the Black Friars?? over top his white habit and his tonsure to better allow God to see his thoughts and to demonstrate his renunciation of worldly aesthetics. From his outstretched hands, a banderole twirls upwards around a now faded woman?s face framed in the blue associated with the Virgin. The leaf is blank on the back. These two features? the heavy fading in a specific area and the blank verso? make suggestions about the production and the reception of the book.This portrait leaf was likely a bespoke product that was tipped into an on-spec, ready-to-buy book. That is to say, at this point, books were no longer being made entirely to the patron?s demand; books had become commodities that more people could afford, so a stationer would have books ready made with minor customization available (such as the addition of a patron portrait). This addition, without text on the back, would not interrupt the flow of the set selection of prayers in the Book of Hours. With this customization the owner literally sees himself in his daily worship of the Virgin Mary. Here is where the importance of the fading comes into play.This is likely not just the wear and tear of history, but the toll of the owner?s ritual touching of the Virgin?s face in conjunction with his portrait. This action is called ?affective piety,? and though chiefly associated with women?s rituals, it was not uncommon for men, particularly those aligned with mysticism, to engage in this method of worship. In the same way that Saint Dominic?s Order responded to the rise of cities in the thirteenth century, affective piety provides a new way of interacting with Christianity. As people moved towards understanding Christ as a man and through his bodily identity, they also moved towards an ?emotional understanding of.