Artículos relacionados a Israel at Sixty: An Oral History of a Nation Reborn

Sinopsis

"Sinopsis" puede pertenecer a otra edición de este libro.

Acerca del autor

Deborah Hart Strober and Gerald S. Strober are the authors of Giuliani: Flawed or Flawless? The Oral Biography; His Holiness the Dalai Lama: The Oral Biography; and five other oral histories. They live in New York City.

De la contraportada

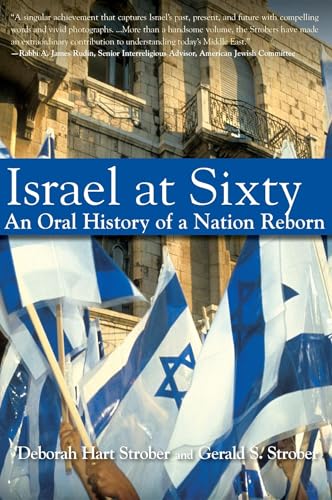

What could celebrate Israel's sixtieth anniversary more aptly than a stirring history of the nation told by the people who lived it? Based on extensive interviews, Israel at Sixty presents a balanced, comprehensive account of this complex and amazing land. It re-creates historic events from the actions of Israel's founding visionaries through the ravages of six wars with its Arab neighbors to its growing strength and international stature and efforts to make permanent peace with its adversaries.

This compelling account begins with that overwhelming moment on May 14, 1948, when David Ben-Gurion rose in the Tel Aviv Opera House to read the Proclamation of Independence of the New Jewish State, to be known as Israel. A flashback to the hopeful and bitter first half of the twentieth century reveals little-known examples of the Zionist spirit of sabras, the ingathered exiles, and Diaspora Jews.

Dan Pattir tells the story of how his parents met when his father rushed to help defend an embattled village from Arab attack in 1929; Yehuda Avner explains how his Zionism, already strong, reached even higher levels when he helped care for child Holocaust survivors in Manchester, England, just after the war; and Joshua Matza recalls his adventures as a fourteen-year-old member of the underground, fighting the British. Holocaust survivors tell harrowing tales of persecution, heart-wrenching loss, soul-searing displacement, and the eventual exhilaration and triumph of their arrival in Israel.

More history comes to life as Israel's first citizens fight off Arab attacks, define modern Israeli culture, find ways to absorb hundreds of thousands of Diaspora Jews flocking to their shores, and build a strong, democratic government. From the bustling streets of Tel Aviv to the quiet communal life of the kibbutz, you will watch as the nation grows, struggles, triumphs, celebrates, and moves on to greater struggles.

Along the way, you will meet such memorable figures as Menachem Begin, Golda Meir, and Yitzhak Rabin through the eyes of those who knew and worked with them. You will relive the stunning victories of the Six-Day War and the Yom Kippur War; the thrilling hopes generated by the Camp David and Oslo accords; and the grim realities of terrorist attacks, intifada, and the continued refusal of Arab extremists to acknowledge Israel's right to exist.

Complete with more than fifty previously unpublished photos, Israel at Sixty is a beautiful keepsake for anyone who loves, respects, and supports the Jewish state.

De la solapa interior

What could celebrate Israel's sixtieth anniversary more aptly than a stirring history of the nation told by the people who lived it? Based on extensive interviews, Israel at Sixty presents a balanced, comprehensive account of this complex and amazing land. It re-creates historic events from the actions of Israel's founding visionaries through the ravages of six wars with its Arab neighbors to its growing strength and international stature and efforts to make permanent peace with its adversaries.

This compelling account begins with that overwhelming moment on May 14, 1948, when David Ben-Gurion rose in the Tel Aviv Opera House to read the Proclamation of Independence of the New Jewish State, to be known as Israel. A flashback to the hopeful and bitter first half of the twentieth century reveals little-known examples of the Zionist spirit of sabras, the ingathered exiles, and Diaspora Jews.

Dan Pattir tells the story of how his parents met when his father rushed to help defend an embattled village from Arab attack in 1929; Yehuda Avner explains how his Zionism, already strong, reached even higher levels when he helped care for child Holocaust survivors in Manchester, England, just after the war; and Joshua Matza recalls his adventures as a fourteen-year-old member of the underground, fighting the British. Holocaust survivors tell harrowing tales of persecution, heart-wrenching loss, soul-searing displacement, and the eventual exhilaration and triumph of their arrival in Israel.

More history comes to life as Israel's first citizens fight off Arab attacks, define modern Israeli culture, find ways to absorb hundreds of thousands of Diaspora Jews flocking to their shores, and build a strong, democratic government. From the bustling streets of Tel Aviv to the quiet communal life of the kibbutz, you will watch as the nation grows, struggles, triumphs, celebrates, and moves on to greater struggles.

Along the way, you will meet such memorable figures as Menachem Begin, Golda Meir, and Yitzhak Rabin through the eyes of those who knew and worked with them. You will relive the stunning victories of the Six-Day War and the Yom Kippur War; the thrilling hopes generated by the Camp David and Oslo accords; and the grim realities of terrorist attacks, intifada, and the continued refusal of Arab extremists to acknowledge Israel's right to exist.

Complete with more than fifty previously unpublished photos, Israel at Sixty is a beautiful keepsake for anyone who loves, respects, and supports the Jewish state.

Fragmento. © Reproducción autorizada. Todos los derechos reservados.

Israel at Sixty

An Oral History of a Nation RebornBy Deborah Hart Strober Gerald S. StroberJohn Wiley & Sons

Copyright © 2008 Deborah Hart StroberAll right reserved.

ISBN: 978-0-470-05314-0

Chapter One

THE PERSECUTION OF EUROPEAN JEWRY AND FINDING SAFE HAVENS

Adolf Hitler's "Final Solution"-the chilling code words for his hoped-for destruction of European Jewry-would not be felt in its full horror until the 1940s, following the outbreak of World War II, with the full mechanization of his death camps. The Nazi Holocaust was preordained, however, when on January 30, 1933, Adolf Hitler and his murderous minions assumed power in Germany.

The most terrible era in the history of the Jewish people would end only with the unconditional surrender on May 8, 1945, of the remnant of the regime that had for more than twelve years systematically dehumanized, terrorized, ghettoized, and then deported Jews from Nazi-occupied nations, annihilating approximately six million, including more than one million children.

Setting the Stage for the Near-Annihilation of European Jewry

At twelve thirty a.m. on Friday, September 30, 1938, the British prime minister, Arthur Neville Chamberlain (1869-1940), affixed his signature to the Munich Pact, an act of appeasement toward Hitler, in which the Sudetenland was ceded to Germany, effectively dismembering Czechoslovakia. Hours later, Chamberlain returned to Britain, waving a piece of paper and declaring that his efforts had achieved "Peace for our time."

Shmuel "Meuki" Katz, migr from South Africa to Eretz Israel, 1936; member, High Command, Irgun Zvai Leumi, 1944-1948; member, first Knesset, 1948-1952; founding member, Land of Israel Movement; cabinet member and adviser to Prime Minister Menachem Begin on overseas information, 1977-1979; publisher; author; columnist, Jerusalem Post; biographer of Ze'ev Jabotinsky I arrived in London on the day that Chamberlain arrived from Munich and so I was witness to the euphoria that overtook the public-I don't know how much of the public-at Chamberlain's success in staving off war. I was staying at a hotel near Piccadilly Circus. It had been raining, and when it stopped raining, toward evening, I went out for a walk. I came across a crowd of young people. Apparently, they had all been in pubs, or whatever, and were singing, "For He's a Jolly Good Fellow" and "Good Old Neville." I was on one sidewalk, and opposite me, on the other sidewalk, was a dark-haired guy who was dishing out leaflets. So I walked across and took one from him. The heading was "Czechoslovakia Betrayed." The crowd came up around us, and he gave some of them leaflets. They started joking at him; they didn't hit him or anything but were laughing at him, jeering at him, and one of them apparently patted him on the back or perhaps had given him a push. He fell and, as it had been raining, the papers all got wet. His glasses fell off, and he put them back on again. Then he walked away very dejectedly, and I remember thinking to myself, This is the only sane man in the street.

The Situation in Eastern Europe

The Jewish population of Lodz, located in central Poland and the center of the country's textile industry, had grown from 11 people in the late eighteenth century to 233,000 at the outbreak of World War II, comprising a third of the city's population. Following the Nazi Wehrmacht's entry into the city on September 8, 1939, Lodz was annexed by the Reich, its Jewish Community Council was disbanded, and the organization's former vice chairman, Chaim Rumkowsky, was installed as Judenaltester (Jewish community "elder"). Within weeks the Nazis had disbanded this new organization, sending its members to a concentration camp. Further acts of terror were carried out against the city's Jewish community, including cruel and murderous ghettoization, vicious pogroms, and deportations to Chelmno, a notorious death camp. By September 1, 1944, most of the ghetto's remaining population of 76,701 had been deported to Auschwitz. When Soviet troops liberated the ghetto on January 19, 1945, only 800 Jews were found there.

Shmuel Katz We [Mr. Katz and his mentor, the Revisionist visionary Ze'ev "Jabo"-a popular nickname for Jabotinsky] came to Lodz [in 1936], where he [Jabotinsky] was staying with a family named Spektor [the family of Jacob Spektor, a wealthy textile merchant and prominent Revisionist, whose son Eryk would one day live in New York and become the head of Herut, "Freedom," U.S.A., the organization established in July 1948 in Israel by the Irgun]. They had an extra room-I think that Eryk was then studying in Jerusalem-and Jabo was to deliver a talk in a cinema in the town, so we all went together with Jabo. They had a car, an unusual thing in Poland, and when we arrived at the cinema, the whole area was full of people protesting against Jabotinsky because he was telling them to get the hell out of Europe. And their argument was: "We're Polish; we've been here a thousand years!" We couldn't get into the front entrance of the cinema; the crowd was too thick. So there were police around. A big policeman-I remember him very well-took us around to the back of the cinema. There was a kind of yard behind the cinema, and there was still a crowd back there. It wasn't very thick, and so the policeman told us to wait. He took Mrs. Spektor and led her into the hall through the back entrance. Then he took Jabotinsky and led him into the hall, through the same entrance. Then he came back and took Mr. Spektor. When he didn't come back again, I was left there with the crowd between me and the hall. They wouldn't let me through, so I started pushing my way toward the cinema. The policeman had stationed himself near the hall, and when he saw that somebody was making some kind of disturbance at the back entrance, he came around and saw me pushing through the crowd. He gave me one punch, just one, and I flew across the empty space, onto the sidewalk, and sat there. Then I saw that Jabo, who had already been inside the hall, had come out and was looking for me. Finally, he saw me, and I could see that he wanted to laugh, but he restrained himself. He called the policeman, and the policeman came up to me and led me into the hall like a little boy. And that's the occasion when I heard Jabotinsky speak to a partly unsympathetic audience. They didn't like what he was telling them-some did, some didn't-but it was not the enthusiasm that I had seen at other meetings with Jabotinsky.

Matityahu "Mati" Drobles (with Batia Leshem, interpreter), Polish-born Holocaust survivor; immigrated to Israel, 1950; chairman, Rural Settlements Division, World Zionist Organization; chairman, Central Zionist Archive It was a very, very bad time. When the war began, I was [nearly] seven years old. I came from a good family, of average income. I was in the middle; my sister was two and a half years older, and my brother was two years younger. In 1941, the Germans took us to the ghetto. The whole family-there were 250 people-was killed, but we three children survived.

In the winter of '42, we escaped the ghetto through the garbage, and for three years we wandered through villages and forests-no housing, no place to live. I was nine years old; my sister was nearly twelve years old. We wanted to stay in our Jewish life, but we didn't meet any Jews, and we were convinced that there were no Jews anymore in the world. I was talking with my sister: "What will happen? There are no Jews anywhere in the world." She said, "You know what? I know one place in the world, called Palestine. There, I heard that Jews are living. When the war is finished, we are going to Palestine."

The Situation in Germany

Simcha Waisman, born in Palestine to immigrants from Europe in 1945; joined the Israeli navy at the age of fifteen; served in the 1967 Six-Day War; emigrated to the United States two years later; owner of a print shop in New York City for thirty-five years until retiring in mid-2006; currently, community activist, volunteer with the Richmond Hill Block Association, Queens, New York My mother was a registered nurse in Germany. She was one of twelve brothers and sisters, a large family. I met some of my mother's side, her brothers and sisters-they came to Israel later on-and we used to live like a big family. But some of them I never met because they didn't make it; my mother's parents never made it out from the Holocaust.

Shabtai Shavit, Arabic speaker; former head of Mossad Both my mother's and my father's families perished in the Holocaust. My mother was one of eight children, and only one of them survived. In the fifties, he immigrated to Israel. And he succeeded in saving his wife, his daughter, and his wife's sister, and all of them came to Israel.

Malcolm Hoenlein, founding executive director, Greater New York Conference on Soviet Jewry; founding executive director, Jewish Community Relations Council of Greater New York; at present, executive vice chairman, Conference of Presidents of Major American Jewish Organizations My grandparents were all killed. My father came [to the United States] in June 1940 from Holland. He lost his sister, as well, and a nephew and a brother-in-law. Only one sister survived. My mother was an only child, and her mother and many other relatives were killed. [My family had lived] there for many hundreds of years, much longer than the people who killed them.

Ernest Stock, Ph.D., German-born immigrant to the United States and then to Israel; journalist, Jerusalem Post; assistant to the director (United States), Hillel Foundations; official, Jewish Agency for Israel; prolific author; husband of Bracha Stock We got out quite late, after the Crystal Night in Germany in 1938. My father was very hesitant to leave. He was already in his midforties-he was born in 1892-when the Nazis came to power. Now a man in his forties is still considered young, but back then a man at that age would find it quite a difficult move. In fact, I came across something that my father had written, in which he said, "If I had known earlier that it was that easy to become adjusted in America, I would have left Germany earlier." He must have had a mind-set that said, It's going to be terrifically difficult. And another thing, he was a perpetual optimist who felt, This whole business with the Nazis is bound to blow over; the Germans, after all, are not that crazy that they would fall for this guy and let him take over completely. I left Germany at age fourteen with my sister, for France, while my father was in a concentration camp, and my mother was left behind. She let us go to France with the idea that we would somehow all get together and go to America afterward.

Bobby Brown, immigrant to Israel from the United States, 1978; mayor, settlement of Tekoah; aide to Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu; currently, adviser to the treasurer, Jewish Agency for Israel My parents came very late, separately. My mother was twelve years old when she came with her mother to the United States. They had the highest numbers on the last legal boat to leave Germany, and they left in April 1940. And there were stories. My grandfather had actually been a leader in a small town called Battenberg, and he had been called in by the Nazis for interrogation. They kept him for a day, and he came home feeling very badly and went to sleep. When he woke up, he died. No one ever knew exactly what happened or found out from the Gestapo. The only doctor in town was a leader in the Nazi Party, so he refused even to come to examine my grandfather's body. And after not seeing my grandfather, the doctor wrote: "Cause of death: heart attack." There was one cemetery for three towns, and on the way, the funeral procession was stoned, and the kids were screaming: "That's the father. When's the mother coming?"

When my grandfather died, the request to leave had been submitted in his name. His name was Ludwig, so he was Ludwig I. Neuberger-the "I" was for "Israel," which was the name all Jewish men had to write; Jewish women had to write "Sarah"-so my grandmother all of a sudden realized that she'd have to start the whole process over because he had requested it, and now he was dead. She bribed someone to change the "I" to "Inger," which was my mother's name, so that it said, "Ludwig Inger," and then she convinced them that since there was an application from "Inger," she was now the custodian for Inger, so they let her continue in that queue, waiting for numbers to get out. Obviously, had she not done that, and if they hadn't gotten out in April 1940, they wouldn't have gotten out.

After a lot of problems, my grandmother and my mother took a boat from Hamburg to Genoa. There they had to wait three days until another boat took them to the United States. They knew no one in New York; they lived in a public park and ate from garbage cans.

My grandmother's brother lived in Germany with only one desire, and that desire was to get his son out. After working really very hard at it, he got his son on a Kindertransport to England. But that Kindertransport was torpedoed, and all the kids were killed. When my grandmother's brother heard that, he hanged himself. My grandmother knew that her brother had died, but she never knew the reason why-no one ever told her.

My father's mother was a nurse in World War I, and one of her patients was the young prince Haile Selassie [1892-1975, the emperor of Ethiopia from 1930 to 1936 and again from 1941 to 1974. Known as the Lion of Judah, he had close ties with Israel until succumbing at the time of the Yom Kippur War to an Arab inducement to support him in his difficulties with insurgent elements. In 1974, he was deposed by a Marxist council, imprisoned and, reportedly, murdered.]. So when the time came to leave-she was just trying to go anywhere-she actually wrote to Haile Selassie and asked whether he would take in the family on my father's side as refugees. He wrote back, "I remember you with great fondness, but it is not a good time to come to Ethiopia." And, of course, a few months later, Ethiopia was invaded by the Italians. He probably knew that that would happen. Otherwise, I might have been the only albino Ethiopian.

My grandparents lived in a small town near Fulda. My grandfather was a big, strapping man-he was a cattleman. When the Nazis came in the early days to his house, he took a chair and broke it and started beating them up. Maybe a couple of years later, that would have been enough to end him, but in the very beginning, the Nazis didn't really know what to do, and they ran away.

They let my grandmother and three children leave the country, but not my father, because he was of military age. And she said, "What do you mean `military age' for a Jewish boy?" So the Nazis said that "military age" meant that he would have to go into a labor battalion. And those who went into labor battalions usually didn't come out. My grandmother told my grandfather, "You're not leaving; you're staying with Lothar until he gets out." The way the Nazis stopped him from getting out was that they wouldn't give him a passport. So every few weeks, my grandfather would go to the Passport Office, and they would always refuse him, and he'd go back. My grandfather sold cattle, and once, when he was leaving the Passport Office, the head of the Cattlemen's Association saw him and said, "Bernard, what are you doing here?" My grandfather explained the situation, and the head of the Cattlemen's Association said, "I'm also the president of the Passport Office, and if you come tomorrow, I'll give a passport to your son." On Shabbat, the next day, my grandfather asked, "What shall I do?" And my grandmother said, "You get on your bicycle and pedal over to that Passport Office!" Sure enough, there was a passport waiting for him, and my father got out. Who lived and who died was a matter of luck.

(Continues...)

Excerpted from Israel at Sixtyby Deborah Hart Strober Gerald S. Strober Copyright © 2008 by Deborah Hart Strober. Excerpted by permission.

All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Excerpts are provided by Dial-A-Book Inc. solely for the personal use of visitors to this web site.

"Sobre este título" puede pertenecer a otra edición de este libro.

EUR 10,70 gastos de envío desde Estados Unidos de America a España

Destinos, gastos y plazos de envíoComprar nuevo

Ver este artículoEUR 10,79 gastos de envío desde Estados Unidos de America a España

Destinos, gastos y plazos de envíoResultados de la búsqueda para Israel at Sixty: An Oral History of a Nation Reborn

Israel at Sixty: An Oral History of a Nation Reborn

Librería: ThriftBooks-Dallas, Dallas, TX, Estados Unidos de America

Hardcover. Condición: Very Good. No Jacket. May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 1.65. Nº de ref. del artículo: G0470053143I4N00

Cantidad disponible: 1 disponibles

Israel at Sixty: An Oral History of a Nation Reborn

Librería: ThriftBooks-Dallas, Dallas, TX, Estados Unidos de America

Hardcover. Condición: Good. No Jacket. Pages can have notes/highlighting. Spine may show signs of wear. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 1.65. Nº de ref. del artículo: G0470053143I3N00

Cantidad disponible: 1 disponibles

Israel at Sixty: An Oral History of a Nation Reborn

Librería: The Secret Book and Record Store, Dublin, DUB, Irlanda

Hardcover. Condición: Very Good. Estado de la sobrecubierta: Good. Text block very slightly stained but internally clean. Bottom right corner of dust jacket very slightly torn. Front cover of dust jacket has a sticker. Spine is creased. Corners, edges and spine bumped. Overall in very good condition. Nº de ref. del artículo: AAP015

Cantidad disponible: 1 disponibles

Israel at Sixty : An Oral History of a Nation Reborn

Librería: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, Estados Unidos de America

Condición: Good. 1st Edition. Used book that is in clean, average condition without any missing pages. Nº de ref. del artículo: 51057867-6

Cantidad disponible: 2 disponibles

Israel at Sixty : An Oral History of a Nation Reborn

Librería: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, Estados Unidos de America

Condición: Good. 1st Edition. Former library book; may include library markings. Used book that is in clean, average condition without any missing pages. Nº de ref. del artículo: GRP76446959

Cantidad disponible: 1 disponibles

Israel at Sixty: An Oral History of a Nation Reborn

Librería: Wonder Book, Frederick, MD, Estados Unidos de America

Condición: Very Good. Very Good condition. Very Good dust jacket. A copy that may have a few cosmetic defects. May also contain light spine creasing or a few markings such as an owner's name, short gifter's inscription or light stamp. Bundled media such as CDs, DVDs, floppy disks or access codes may not be included. Nº de ref. del artículo: N24B-03625

Cantidad disponible: 1 disponibles

Israel at Sixty: A Pictorial and Oral History of a Nation Reborn (Hardback or Cased Book)

Librería: BargainBookStores, Grand Rapids, MI, Estados Unidos de America

Hardback or Cased Book. Condición: New. Israel at Sixty: A Pictorial and Oral History of a Nation Reborn 1.56. Book. Nº de ref. del artículo: BBS-9780470053140

Cantidad disponible: 5 disponibles

Israel at Sixty: An Oral History of a Nation Reborn

Librería: Kennys Bookshop and Art Galleries Ltd., Galway, GY, Irlanda

Condición: New. 2008. 1st Edition. hardcover. . . . . . Nº de ref. del artículo: V9780470053140

Cantidad disponible: 15 disponibles

Israel at Sixty: An Oral History of a Nation Reborn

Librería: The Maryland Book Bank, Baltimore, MD, Estados Unidos de America

hardcover. Condición: Very Good. 1st Edition. Used - Very Good. Nº de ref. del artículo: 5-U-5-0367

Cantidad disponible: 1 disponibles

Israel at Sixty: An Oral History of a Nation Reborn

Librería: Kennys Bookstore, Olney, MD, Estados Unidos de America

Condición: New. 2008. 1st Edition. hardcover. . . . . . Books ship from the US and Ireland. Nº de ref. del artículo: V9780470053140

Cantidad disponible: 15 disponibles