GALILEI, GALILEO & CASTELLI, BENEDETTO (1 resultados)

Tipo de artículo

- Todo tipo de artículos

- Libros (1)

- Revistas y publicaciones

- Cómics

- Partituras

- Arte, grabados y pósters

- Fotografías

- Mapas

-

Manuscritos y

coleccionismo de papel

Condición

- Todo

- Nuevos

- Antiguos o usados

Encuadernación

- Todo

- Tapa dura

- Tapa blanda

Más atributos

- Primera edición

- Firmado

- Sobrecubierta

- Con imágenes del vendedor

- Sin impresión bajo demanda

Ubicación del vendedor

Valoración de los vendedores

-

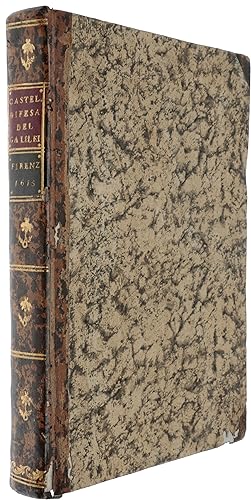

Risposta alle opposizioni del S. Lodovico delle Colombe, e des S. Vincenzio di Grazia, contro al trattato del Sig. Galileo Galilei, delle cose che stanno su l'acqua o che in quella si muovono . Nella quale si contengono molte considerazioni filosofiche remote dalle vulgate opinioni

Publicado por Cosimo Giunti, Florence, 1615

Librería: SOPHIA RARE BOOKS, Koebenhavn V, Dinamarca

Miembro de asociación: ILAB

Original o primera edición

First edition. THE BUOYANCY DISPUTE - GALILEO REPLIES TO HIS CRITICS. First edition, rare, from the Riccati library, of Galileo's principal text on the controversy over floating bodies. This work was written as a reply to two attacks by Delle Colombe (1565-1623) and Di Grazia on Galileo's 1612 treatise on floating bodies, Discorso . intorno alle cose che stanno ub su l'acqua, o in quella si muovono. Although Galileo drafted replies to these (as well as two other polemical attacks on his treatise), this was the only one to be published. Like several of his polemics of this period, it appeared under the name of a colleague, in this case his pupil and friend Castelli (1578-1643). "Shortly after his return to Florence, Galileo became involved in a controversy over floating bodies. In that controversy an important role was played by Colombe, who became the leader of a group of dissident professors and intriguing courtiers that resented Galileo's position at court. Maffeo Barberini-then a cardinal but later to become pope-took Galileo's side in the dispute. Turning again to physics, Galileo composed and published a book on the behavior of bodies placed in water, in support of Archimedes and against Aristotle, of which two editions appeared in 1612. Using the concept of moment and the principle of virtual velocities, Galileo extended the scope of the Archimedean work beyond purely hydrostatic considerations . The book on bodies in water drew attacks from four Aristotelian professors at Florence and Pisa, while a book strongly supporting Galileo's position appeared at Rome. Galileo prepared answers to his critics, which he turned over to Castelli for publication in order to avoid personal involvement. Detailed replies to two of them (Colombe and Grazia), written principally by Galileo himself, appeared anonymously in 1615, with a prefatory note by Castelli implying that he was the author and that Galileo would have been more severe" (DSB). In the present reply to his academic critics, Galileo both enlarged the scientific reasoning behind his position and presented a vigorous philosophical defence of that position. In the second reply to Grazia, Galileo states that he made use of two basic principles, "that equal weights moved with equal speed are of like power in their effects, and that greater heaviness of one body could be offset by greater speed of another" (Stillman Drake). This copy contains the rare two additional leaves (Y2) completing the errata and giving the registration and printer's device, not recorded by Cinti. Provenance: From the library of the Riccati family (bookplate on front paste-down), whose most prominent bibliophile members were Jacopo Francesco Riccati (1676-1754) and his son Vincenzo (1707-75), both mathematicians and physicists. "About the first week in August [1611] a memorable dispute arose between Galileo and some philosophers over the conditions governing the floating and sinking of bodies in water . Galileo, his friend Filippo Salviati, and two professors of the University of Pisa were discussing condensation when one of the professors, Vincenzio di Grazia, brought up the example of ice, which he considered to be simply condensed water. Galileo replied that ice should rather be regarded as rarefied water, since ice floats and must therefore be less dense than water. The professors contended that ice floated because of its broad flat shape, which made it impossible for the ice to cleave-downward through the water. Galileo pointed out that ice held forcibly under water and then released seemed to manage to cleave through it upward, even though then its own weight ought to help hold it down. When it was argued that a sword struck flat on water resists, while edgewise it cuts easily through water, Galileo explained the irrelevance of this observation. He granted that the speed of motion through water was indeed affected by shape, as Aristotle himself had said, but not the simple fact of rising or sinking through water, which was the point at issue. Water offered resistance not to division, but to speed of division, while spontaneous rising or sinking of solids in water was governed only by the Archimedean principle. This discussion did not convince the professors. "Three days later, Di Grazia told Galileo that he had met someone who said he could show Galileo by experiments that shape did play a role in floating and sinking in water; this was Colombe, who had not been present at the initial conversation. Galileo wrote out the conditions of the contest: Colombe was to show by experiment that a sphere of some material that sank in water would not sink if the same material were given some other shape. Canon Francesco Nori was to referee the experiments presented by both sides. Colombe added the stipulation that he would decide on the material and shapes to be used, the material to be of nearly the same density as water itself, and Filippo Arrighetti was made co-judge with Nori. "During the next few days Colombe exhibited to many people his experiments, made with lamina, spheres, and cylinders of ebony. Galileo perceived that the contest was going to become a verbal one in this way; the real issue concerned the rising or sinking of bodies placed in water, not the behavior of bodies placed on its surface and incompletely wetted. Presumably he had the support of the referees on this, because when the meeting at Nori's house was scheduled, Colombe failed to appear. Galileo then sent to Colombe a newly worded challenge, specifying that all the materials used were to be placed entirely in the water before each experiment with them. A date was set for the meeting, this time at Salviati's house in Florence (not at his villa, several miles distant from the city). "By this time gossip about the contest came to the attention of Cosimo de' Medici, who told Galileo not to engage in public disputes but rather to write out his arguments in a dignified form worthy of a court representative. When the s.