Descripción

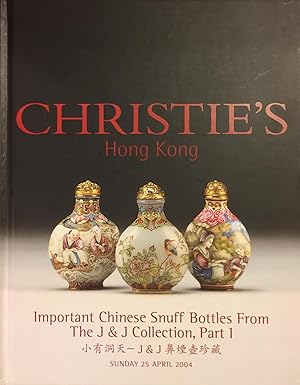

English text; Hardcover (without dust jacket, as issued); 21.8 x 27.7 cm; 1.022 Kg; 190 pages with lots from 801 to 808 all with colour illustration.; Signs of wear. Minimal edgeworn. No markings, writing or highlighting on the interior except for one page that shows signs of have been bent.; Auction catalogue.; Foreword by James Li and introduction by Hugh Moss; The elevation to art of the Chinese snuff bottle began at the Court of the Kangxi Emperor in the late seventeenth century. Addicted to snuff throughout the dynasty, the rulers of the Middle Kingdom fostered the habit, devising exquisite, highly artistic containers in which to keep their precious powder in perfect condition and readily to hand. Naturally, snuffing became widespread among the Official Class and, as that vast body of highly literate civil servants was posted around the Empire and as they returned to their homes after the service, they spread the habit far and wide. By the mid-Qing period addiction to snuff had spread throughout the Empire, and, encouraged by Imperial example, two Imperial trends spread with it: the production of artistic containers to hold the snuff; and collecting snuff bottles, usually in far greater numbers than function alone required. Although the production of fine snuff bottles become wide-spread by the latter part of the eighteenth century, reaching far beyond the Court, Imperial demand continued to the end of the dynasty in 1911. Initially a great deal of this production came out of the Imperial workshops located at the Court (within the Forbidden City, in the Imperial City which enclosed it, and at the Yuanming yuan the Imperial Gardens to the West of Beijing). The Imperial glass manufactory, set up in 1796 with the help of Kilian Stumpft and his fellow Missionaries, was probably responsible for well over half of all Imperial snuff bottles produced during the eighteenth century, sometimes responding to orders as large as five hundred bottles for distribution as fits on a single, festive occasion. Glass and other hard-stones, including jade, were carved at the Court lapidary workshop, while others were produced in workshops for lacquer, wood, ivory and among the jewels of eighteenth century Imperial production enamels on metal and glass. The Court was also supplied by distant Imperial facilities at Guangzhou, Suzhou, Yangzhou, Jingdezhen, and elsewhere. Orders placed around the country, combined with regular tribute from high officials in all the major artistic centres, swelled the Imperial collection and, in part, provided the enormous number of gifts distributed by the Court every year. A great deal of this production was specifically ordered by the Emperor, or produced in response to his taste, reflecting Imperial predilection, style and designs. This large body of snuff bottles, despite difficulties in universal identification, is all Imperial to some extent. There may be a difference in importance and appeal between an enamelled metal bottle, specifically ordered by the Emperor, designed by artist in the Imperial Academy of art, painted by either a Chinese, Court-artist or a Jesuit missionary, and designated as having been made By Imperial Command and a plain jade miniature meiping ( prunus-blossom vase ) carved only with mask handles of an Imperial style and produced for the Court, perhaps even at a distant facility. Both, however, are properly Imperial. Indeed, for all we know the enamelled bottle may have been made as a gift to an official and barely, if at all, brushed the Emperor s palm, while the unassuming jade bottle might have nested in it regularly over the years. excerpt from the introduction by Hugh Moss. N° de ref. del artículo ABE99

Contactar al vendedor

Denunciar este artículo

![]()