Descripción

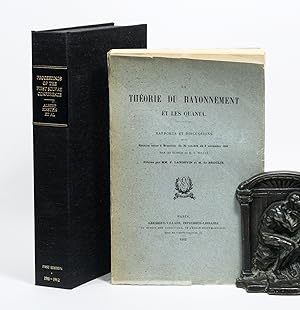

RARE FIRST EDITION IN ORIGINAL WRAPPERS OF THE REPORTS FROM THE HISTORIC FIRST SOLVAY CONFERENCE, "THE FIRST INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE IN PHYSICS EVER ORGANIZED" AND A CRITICAL MOMENT IN THE BIRTH OF QUANTUM PHYSICS. In the short time that followed Planck's hypothesis of the universal constant that would bear his name, the greatest minds in physics were largely at a loss about how to deal with the bizarre theoretical results that followed (let alone the experimental results which confirmed them!). Much of the focus at the time was on black-body radiation, including work by Planck himself, as well as Lorentz, Rayleigh, and Jeans. However, shortly before the first Solvay conference, a young Einstein had also started investigating the related question of materials' specific heat. (Kuhn). "The purpose of the first Solvay Conference was thus two-fold: first, there was the need to examine whether classical theories (molecular-kinetic theory and electrodynamics) could, in some undiscovered ways, provide an explanation of the problem of black-body radiation and of the specific heat of polyatomic substances at low temperatures; secondly, to consider phenomena in which the theory of quanta could be successfully used." (Mehra). Underlying these questions was the more fundamental mystery of how to interpret the existence of the Planck constant. There were two camps, both of which were represented at the conference. Planck's took the constant to indicate some fundamental constraint on the radiative processes of emission and absorption. For example, "Sommerfeld introduced a version of the quantum hypothesis, which he considered to be compatible with classical electrodynamics. He postulated that in 'every purely molecular process' [a quantized] quantity of action is exchanged." (Staumann). Einstein's camp, on the other hand, took the quantum of action to represent the physicality of a (perhaps pseudo-)corpuscular theory of energy exchange - his photons of light. Although the debates that followed the lectures (included in the proceedings) did not rise to the famous heated exchange that Einstein would have with Bohr at the 1927 Solvay conference, we do see some of the young Einstein's hotheadedness as he opens the debate following Planck's plenary lecture: "What I find strange about the way Mr. Planck applies Boltzmann's equation is that he introduces a state probability W without giving this quantity a physical definition. If one proceeds in such a way, then, to begin with, Boltzmann's equation does not have a physical meaning." (As translated by Straumann.) It would take another 14 years for quantum mechanics to be fully formalized, but the first Solvay conference represents a pivotal point in quantum history: "During 1911 [the] situation changed quickly. Articles that applied the quantum to other topics then outnumbered those on blackbody radiation for the first time, and some were backed by impressive experimental evidence. In part because of that evidence, physicists like Planck and Lorentz, who had previously taken the constant h to be characteristic only of the radiation problem, began to consider additional areas in which others had earlier staked quantum claims." (Kuhn). Albert Einstein and the Solvay Conference: Among the most renown scientists of the day - including Ernest Rutherford, Marie Curie, and Max Planck - Einstein made quite an impression. At age 32, he was the second youngest participant in the conference. The youngest was British physicist Frederick Lindemann, later to become scientific adviser to Winston Churchill. Although "Einstein had already published so many masterpieces, none had actually been put to the test and his theories were looked on rather as tours de force than as definitive additions to knowledge. But his pre-eminence among the twelve greatest theoretical physicists of the day was clear to any unprejudiced observer." (Frederick Lindemann, quoted in Brian). References: Headline quote from the Solvay Instit. N° de ref. del artículo 2508

Contactar al vendedor

Denunciar este artículo

![]()