Descripción

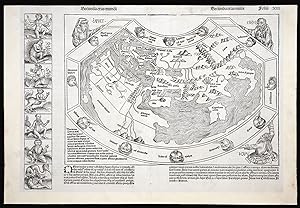

"Outlandish creatures and beings that were thought to inhabit the furthermost parts of the earth". Double-page woodcut map. From the famous 'Chronicle of the World', known as the Nuremberg Chronicle, a history of the world, published the year that Columbus returned to Europe after discovering America. "The world map is a robust woodcut taken from Ptolemy… What gives the map its present-day interest and attraction are the panels representing the outlandish creatures and beings that were thought to inhabit the furthermost parts of the earth. There are seven such scenes to the left of the map and a further fourteen on its reverse" (Shirley). The map is a copy of the Venetian woodcut added to Pomponius Mela's 'Cosmographia' eleven years earlier, and, like the Mela, shows the Portuguese discoveries off the west coast of Africa. The Schedel, however, also includes an unidentified island of this coast. The text of the Nuremberg Chronicle is a year-by-year account of notable events in world history from the creation of the world down to the year of publication. It is a mixture of fact and fantasy, recording events like the invention of printing, but also repeating stories from Herodotus. The world map is decorated in three corners with depictions of the sons of Noah responsible for recolonizing the world after the deluge; Shem, Ham, and Japhet, and the left hand margin displays seven semi-human creatures. These are printed from a separate woodblock and mark the end of a catalogue of human freaks, starting on the preceding page of the 'Chronicle', which derive from the 'Polyhistor' of Solinus (fl. 250 AD). They include a cyclops, and a man with four eyes, a mn without a nose (located in furthest Africa); a man without a head, whose eyes and mouths are in his chest; a man with a dog's head and talons for fingers; and a man with only one leg, but a foot so large that it doubles as a parasol. 645 woodcuts were used to illustrate the Chronicle, but many were used more than once, so there are a total of 1,809 illustrations, making it the most extensively illustrated book of the fifteenth century. The publication history of the Nuremberg Chronicle is perhaps the best documented of any book printed in the fifteenth century, owing to the survival of the contract between the publisher Anton Koberger and his financial partners Sebald Schreyer and Sebastian Kammermeister, the contract between Koberger and the artists, and the manuscript exemplars of both the Latin and German editions (Wilson). The cutters for the illustrations were Michael Wolgemut, his stepson, Wilhelm Pleydenwurff, and their workshop. As Albrecht Dürer was the godson of Anton Koberger and was apprenticed to Wolgemut from 1486 to 1489, it is likely that he was involved in the work. "The Chronicle would appear, at first glance, to follow in the tradition of a conventional structure of human history within the framework of the Bible, in analogy to the six days of creation. A brief Seventh Age follows, reporting the coming of the Antichrist at the end of the world and predicting the Last Judgement. This is followed, somewhat unsystematically, by descriptions of various towns. This narrative pattern conforms with that of the medieval "universal chronicles" written in Latin, as well as with vernacular chronicles. In the known Middle High German chronicles of the world, too, historical events are interwoven with digressions on the subject of natural catastrophes, wars, reports of the founding of cities, etc. Events occurring in other parts of the world are inserted parallel to the biblical stories. Hartmann Schedel chose to place particular emphasis on describing the most important cities of Germany and the Western world. In many cases, we find in the Chronicle the first known illustrations of the cities in question, along with the story of their foundation, the etymology of their names and a painstaking list of facts about the cultural life, economy and trades flourishing there in th. N° de ref. del artículo 13868

Contactar al vendedor

Denunciar este artículo

![]()